How do you assess someone who can’t tell you what they can see?

Optometrist stands beside a visual acuity letter chart. She is pointing towards a letter using a stick with a red bead on the end.

If you have ever been for an eye test, you will be familiar with the standard procedure optometrists use for testing. We ask you some questions about your eye health and general health, eye history, and family history, then we ask you to read the letter chart. We usually ask something like “What is the lowest line of letters you can see clearly?” or “Please read this line of letters”. But what if you can’t read the letters? I don’t mean because they are too blurred, I mean because you have a disability that makes it impossible for you to read a line of letters out loud. Maybe you are non-speaking or minimally verbal, or maybe you have an intellectual disability and the task of reading letters is too complex.

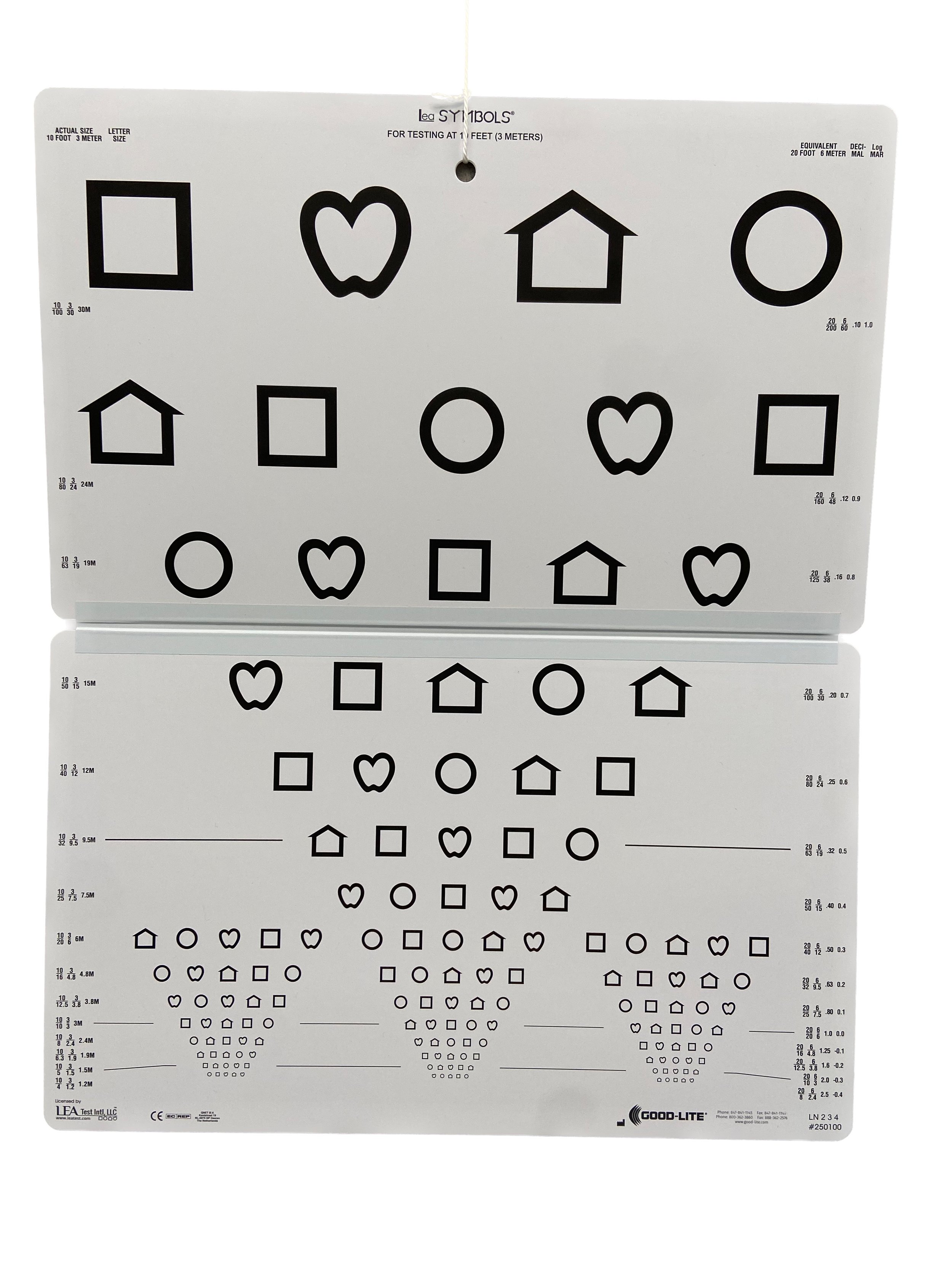

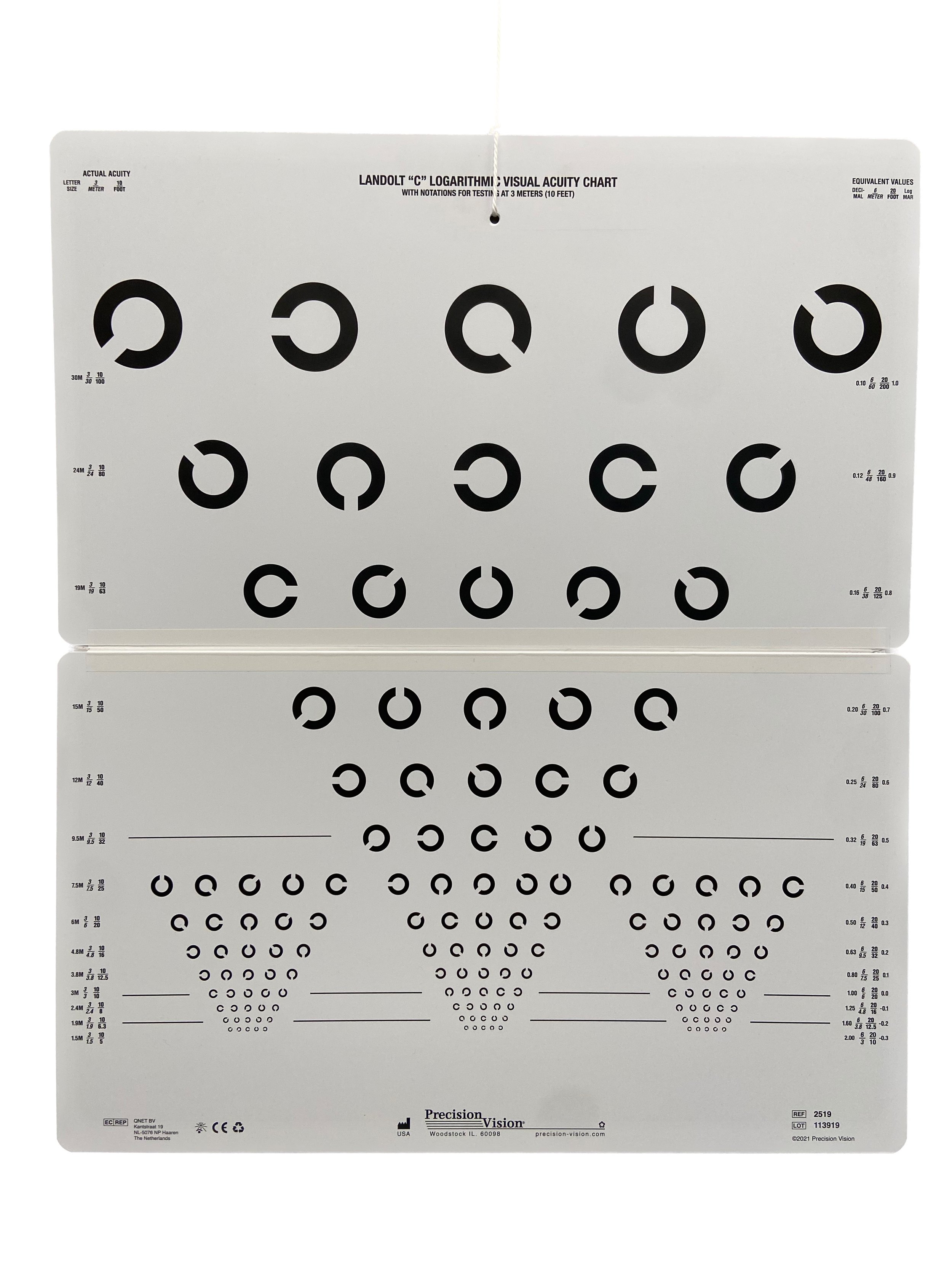

There are actually a lot of alternative methods for assessing vision. If the person being assessed simply doesn’t know the names of the letters of the alphabet, then we can use a similar chart, but with symbols instead of letters. The symbols can be named, or the person can match them using a matching card - “point to the same letter on your card”. There are also charts which comprise a single letter in different orientations, the task is to describe the orientation of the letter. Here are a couple of examples:

Image of the Lea Shapes visual acuity chart. The chart has shapes instead of letters. The shapes are a circle, a square, a house, and a heart/apple shape.

Image of the Landolt C visual acuity chart. The chart displays the letter C in different orientation

Naming shapes or reporting the orientation of a shape or letter does still require significant skills in addition to vision though, and for some people, these may not be a viable alternative. So what then? Well, don’t worry, we have yet more options. Preferential looking tests allow us to assess vision with eye gaze alone, ie. there is no need for the person being assessed to tell us what they can see. With these tests, the person is presented with a visual target which contains ‘detail' and another plain target. Here are some examples:

Image of the Cardiff Low Vision Acuity Test. There is a red box case in the background, and three cards are displayed in front, each card has an image of an apple. The apple is at the top of two of the cards, and at the bottom of the third. At the very front of the image there are two further cards, one has a picture of a ship at the top, the other also has a picture of a ship at the top, but it is almost too faint to see

The Cardiff acuity test consists of a series of cards, each with an ‘optotype’ (a picture) displayed at either the top, or the bottom. The image is created by an outline, which is made up of a thick white line, surrounded by two darker grey lines, each half the width of the white line. If the thickness of the line is too small for you to pick out, then the white and the dark grey with summate, to the same colour as the background, and the image disappears. This is referred to as a vanishing optotype. So how do we use it? The optometrist holds the card up facing the patient, and we observe where the patient is looking. If the person can see the picture, they will look towards it, because that’s just how all us humans are wired. The optometrist watches the patient’s eyes, if their gaze is directed towards the picture, we can be confident they have seen it, and we can conclude that their vision is good enough to distinguish the lines. If the patient cannot see it, we don’t see that clear directional gaze, rather the patient will continue to glance around the room at anything which catches their attention.

Image of an Optometrist holding up a Cardiff card with an image of an apple at the bottom

We present cards with lines of decreasing width until the purposeful gaze towards the picture is not longer observed. From this, we determine what the thinnest line is that the person can see, which in turn allows us to interpret their level of vision. The Cardiff acuity test can be referred to as a ‘preferential looking’ test, because we present a card with an image on one half, and we know that in most cases, people will look towards ‘something’ in preference to nothing, hence, if they can see it, their gaze will be directed towards the picture.

Another example of a preferential looking test, is the Lea Paddles, pictured below.

Image of Lea Paddles: each paddle consists of a circular target containing strips of varying widths with a handle for the examiner to hold. The front target is plain grey

With Lea paddles, we hold up one plain grey paddle, and one striped paddle. If the person we are testing can see the stripes, they will look towards those in preference to the grey, because they are more visually interesting. If they cannot see the stripes, they will glance between the two paddles, or just continue to look towards anything within the immediate vicinity which catches their attention. We reduce the width of the stripes until we no longer see that purposeful gaze towards the striped paddle, we identify the thinnest line the person can see, and this allows us to interpret their level of vision.

Image of an optometrist holding up two Lea paddles, one with wide black and white stripes, and one plain grey

All of the above tests are referred to as ‘standardised’; these tests have been carefully designed to ensure they are repeatable over time, and between different examiners. If you read a letter chart at your eye test one year, and then return for another eye test a year later, you should be able read the same line during each visit, even if you are tested by a different optometrist. If you can no longer read the same line, we know that something has changed and we need to find out what that is.

Standardised tests are always our first choice, but sometimes we have patients who just can’t engage with any of the above tests, and for them, we need to take a more functional approach. Functional vision assessment does not have the repeatability of standardised testing, results can vary from day to day, and you also might get a different result if you are tested by two different people, but it can still provide valuable information in terms of the level of detail the person can see. Actually, because it is more ‘applied’ or real world than standardised tests, it has some benefits over the standardised tests, I mean, how often do you actually need to read a line of letters in the distance, that don’t spell a word? And just because you can do this well, does it actually mean that you can function well visually? Sometimes people can see quite small detail, but still have poor functional vision for other reasons.

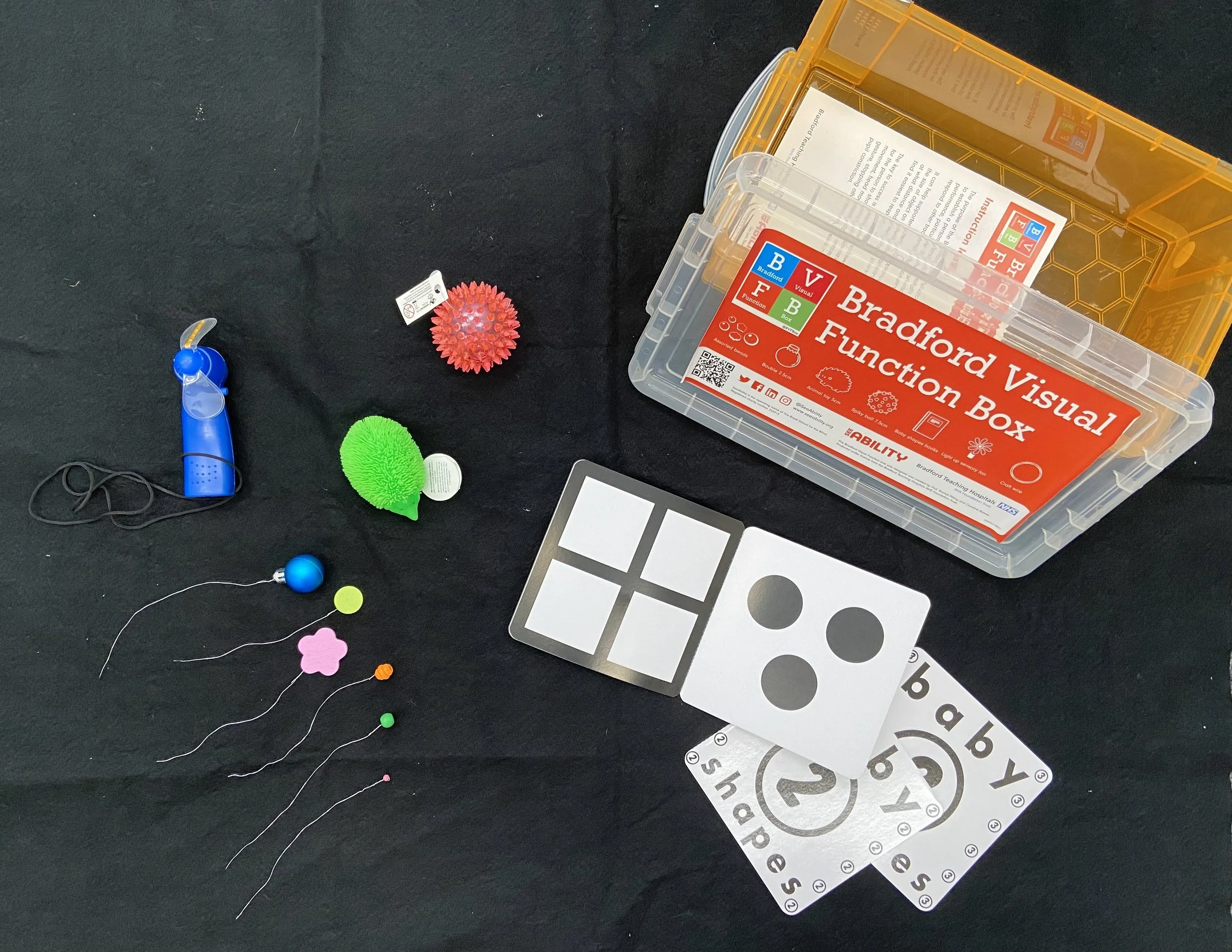

Functional vision assessment can involve monitoring whether or not a person can visually locate and follow a ‘target’ with their eyes. The target might be a small toy, a bead, a lollie, or a picture in a book. We can present different sizes of beads, and determine what is the smallest size bead that the person interacted with. The Bradford Visual Function Box is one example of a functional vision test.

Image of the Bradford Visual Function Box and contents including small brightly coloured toys, light up spinner, black and white baby books, and a series of brightly coloured beads of different sizes attached to bits of wire

The small toys and beads of varying sizes are presented, and we watch to see which the person visually interacts with i.e. which ones they look at. If they don’t look toward the item we are presenting, there is a good chance that it is too small for them to see. That is, providing we are presenting it in the right location: close enough, and in an area where the person’s best vision is located.

Image of an Optometrist holding up a small green bead attached to a thin wire

Assessing functional vision can be as simple as observing how a person navigates an unfamiliar space and what they chose to interact with. So even if someone have very limited ability to participate in our vision tests, we can still glean useful information regarding what they can and cannot see.

If you are interested in learning more about eye tests for someone with complex disability and/or addition needs, please get in touch via phone: 07 35446167, or email: reception@specialeyesvision.com.au.