Understanding Vision in Down Syndrome: More Than Meets the Eye

Image of a young boy with Down syndrome looking towards the camera and smiling.

When we think about vision problems, we often picture issues with the eyes themselves—needing glasses, cataracts, or conditions like strabismus. However, for children with Down syndrome, vision challenges often go beyond the eyes, involving how the brain processes what they see. In this blog, we’ll explore both the well-documented eye conditions associated with Down syndrome and the less commonly recognized—but equally important—visual processing difficulties linked to cerebral visual impairment (CVI).

Ocular Manifestations in Down Syndrome

Children with Down syndrome are at a higher risk for a range of eye conditions. Studies suggest that up to 70% of individuals with Down syndrome experience some form of ocular abnormality. Some of the most common include:

Strabismus (Eye Misalignment): This can appear as inward (esotropia) or outward (exotropia) turning of the eyes, affecting depth perception and coordination.

Refractive Errors: Many children with Down syndrome have hyperopia (longsightedness), myopia (nearsightedness), and/or astigmatism, making early vision assessments crucial.

Keratoconus: This progressive condition causes the cornea to thin and bulge into a cone shape, leading to distorted vision.

Cataracts: While usually associated with aging, cataracts in Down syndrome can develop early, sometimes from birth, affecting clarity of vision.

Hypo-accommodation: Many children with Down Syndrome struggle with focusing on near objects, making tasks like reading or looking at close-up pictures difficult.

Beyond the Eyes: Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI) in Down Syndrome

While eye conditions are often diagnosed and managed with glasses or surgery, many children with Down syndrome experience difficulties that stem from the brain rather than the eyes themselves. This is known as Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI), a condition where the brain has trouble processing visual information. Unlike typical eye conditions, CVI affects how a child interprets what they see, even if their eyesight is technically normal.

Common Signs of CVI in Children with Down Syndrome

Difficulty Navigating Stairs: Many children hesitate or struggle when going down steps, kerbs, or changes in flooring—not due to depth perception issues, but because their brains don’t process the change effectively.

Trouble Finding Objects in Cluttered Spaces: A child may easily spot a toy on an empty table but struggle to find it in a toy box or among other objects.

Overwhelm in Busy Environments: Noisy, visually complex spaces like shopping centers or playgrounds can be disorienting and stressful.

Judging Movement and Speed: Estimating how fast a ball is rolling, how quickly a friend is approaching, or even their own movement can be difficult, leading to clumsiness or defensive behaviors.

Lower Visual Field Deficits: Some children may frequently trip or struggle to notice objects below their eye level.

Why This Matters: Early Recognition and Support

The key to supporting children with Down syndrome and vision challenges is early identification. Regular eye exams are essential, but parents and educators should also be aware of signs of CVI. Because CVI is often mistaken for attention difficulties or behavioral issues, children may not get the support they need. CVI is also not well recognised or understood, despite being the most common cause of visual impairment among children in developed countries. Indeed, CVI frequently goes undetected during a routine eye examination, because the standardised assessments we use during eye examinations are not designed to detect brain-based vision problems. A functional vision assessment with someone who is familiar with CVI is required to properly identify and understand the cerebral component of a child’s vision differences.

Practical Strategies to Help

Declutter Visual Environments: Spacing out toys or using clear organization systems can make it easier for children to find what they need.

Use Predictable Routines: Familiarity reduces visual overload and helps children navigate their surroundings with more confidence.

Provide Verbal Cues: Letting a child know “we’re going up a step now” or “your cup is to the right of your plate” can help bridge visual gaps.

Encourage Contrast and Clarity: High-contrast objects and plain backgrounds can make it easier for children to recognize what they’re looking for.

Getting around: Allowing a child to hold onto your elbow or clothing while moving around, particularly in unfamiliar environments and using lifts rather than stairs where available can help.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the vision challenges faced by individuals with Down syndrome means looking beyond just the eyes. By recognising and identifying both ocular conditions and CVI, we can make adjustments to ensure environments are accessible, supportive, and empowering for these children. Whether through early interventions, environmental adaptations, or simply greater awareness, every small change can make a big difference in how they see—and experience—the world.

Special Eyes Vision Service offers comprehensive functional vision assessments to identify and advise on individualised support for children with suspected CVI.

If you are interested in learning more, please visit our website: www.specialeyesvision.com.au, drop us an email: reception@specialeyesvision.com.au, or call: 07 3544 6167

Not Behavioural Optometry

People often ask me if I am a behavioural optometrist. The answer is no. The next question that usually follows is, "How does what you do differ?" In this blog post, I aim to clarify the key distinctions between my clinical optometry practice and behavioural optometry.

Similarities

While our approaches differ, there are several key areas where my practice and behavioural optometry overlap:

Both aim to maximise visual performance.

Both consider functional vision (how a person uses vision in daily life) as well as visual function (the physiological and neurological processes involved in vision).

Both assess how the eyes work together and test for conditions such as amblyopia (lazy eye) and strabismus (eye turn).

Both work with populations whose development differs from typical patterns.

Both provide support and management strategies for treatable conditions such as strabismus and refractive errors.

Both prescribe glasses when needed.

Key Differences

While there are similarities, our approaches and patient populations are fundamentally different.

Primary Goal and Focus

Behavioural Optometry: Focuses on preventing vision and eye problems from developing or worsening and ensuring that visual abilities needed for everyday tasks such as reading, sports, working, and digital device use are functioning efficiently.

My Clinical Practice: Works to minimise the impact of existing vision problems on function and quality of life, often through environmental modifications rather than direct visual training.

Approach to Binocular Vision

Behavioural Optometry: Aims to improve binocular vision, using vision therapy and exercises to train the eyes to work together more effectively.

My Clinical Practice: Many of my patients cannot attain binocular vision due to neurological or developmental conditions. Instead, we focus on compensatory strategies and environmental adjustments to help them function as effectively as possible.

Methods of Practice

Behavioural Optometry: Often prescribes vision therapy, which involves structured in-office sessions and home exercises over weeks or months to improve eye coordination, focusing, and processing.

My Clinical Practice: Does not prescribe vision therapy, because there are no evidence-based treatments available to my patients. Instead, I identify visual limitations and collaborate with existing support professionals—educators, therapists, and families—to implement appropriate adaptations to daily activities, ensuring full access is possible.

A Different Approach

The Australian College of Behavioural Optometrists (ACBO) states on their website:

"Behavioural Optometry considers your vision in relation to your visual demands, such as reading, computer, and learning to read and write, to ensure your vision is working easily and comfortably."

Similarly, in my clinical practice, I consider vision in relation to what a person wants to use their vision for. However, because I support individuals with disabilities, my assessments focus on determining what they can and cannot see. Vision impairment is highly prevalent among people with disabilities, and often there are no treatments to "fix" the vision issues. Instead, we must find alternative ways to ensure they can access their chosen activities, typically by modifying their visual environment.

The aim is to ensure that visual materials are presented within the limits of what my patients can see through environmental adjustment, for example:

Providing materials in large print format.

Bringing objects closer.

Positioning items within a specific location within a person’s visual field.

Controlling the amount of visual information displayed at once.

Like behavioural optometrists, I assess eye movements, visual perception, and visual processing. However, while behavioural optometry aims to treat these issues when identified, for my patients with disability it is necessary to focus on understanding their impact and make environmental adjustments so that access to visual material is not restricted by them.

There are no recognised treatments for many of the visual challenges faced by my patients. However, when appropriate environmental adjustments are made, we often see significant improvements in function. Considering neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to adapt by reorganising neural networks—there is reason to believe that, in some cases, these types of environmental changes can enhance an individual’s intrinsic functional abilities.

Evidence-Based Practice

Details of the evidence-base for Behavioural Optometry can be found on the ACBO website. My clinical practice is informed by international peer-reviewed research and publications from academic and medical experts in the field.

Final Thoughts

While there are areas of overlap between my clinical optometry practice and behavioural optometry, the differences in patient populations and treatment approaches set us apart. My focus is on individuals with disabilities, ensuring they can engage with their world through tailored environmental adjustments rather than direct visual training. If you or someone you know has complex visual needs, my practice is here to help ensure accessibility and functional vision are optimised.

Different types of vision tests. Part 1: The Cardiff Acuity Test

Image of the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test: Low Vision Edition. A red file box with a handle at the top. On the front is a label which reads ‘The Cardiff Low Vision Acuity Test’ and displays the logo for Cardiff University. In the foreground are some of the grey rectangular vision cards: a set with an image of an apple, and a set with an image of a boat.

Understanding the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test: A Simple and Effective Way to Check Your Child’s Vision

If you've ever wondered how vision is tested in very young children or individuals who can’t speak, you might be interested in the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test. This unique and innovative test is designed to measure vision in a way that’s easy, effective, and non-invasive for people who may have trouble with traditional eye tests.

Let’s break it down simply so you can understand how it works and why it’s so helpful!

What is the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test?

The Cardiff Visual Acuity Test is a special type of vision test that’s perfect for young children, especially those between the ages of one and three, or individuals who might have a disability that makes it hard to communicate. Unlike the usual vision tests where patients need to read letters or numbers, the Cardiff test uses pictures and tracks where the person is looking to see if they can make out the image.

The test is based on something we all do naturally: we tend to look at things that are more interesting, like patterns or pictures, rather than a plain background. This is known as preferential looking, a method used in vision testing where a person is more likely to look at a stimulus they can see rather than a blank or uniform background. The Cardiff Visual Acuity Test takes advantage of this natural instinct to help us understand how well someone sees.

How Does the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test Work?

Here’s how it works in simple terms:

The test uses cards with pictures on them. The pictures could be things like an apple, a boat, or a car, drawn with outlines made of thick and thin lines.

These pictures are on grey cards, and the important part is how the lines are drawn, comprising a central thick white line, surrounded by two thinner, dark grey lines. If someone has good vision, they’ll be able to detect the lines and recognize the shape.

The images used in the test are a form of vanishing optotype, which means that as the lines become thinner, they eventually blend into the background and "vanish" for someone with reduced vision. This helps to determine the smallest level of detail a person can see.

The cards are presented in a way that the picture can either be at the top or bottom of the card. The person being tested won’t be asked to say anything. Instead, the doctor or optometrist will watch where the person’s eyes go. If they look toward the picture, it means they can see it, and the doctor can determine their level of vision from there.

Why is it Great for Young Children and Those with Disabilities?

This test is perfect for children who are too young to read or speak. Since the test relies on where they look rather than what they can say, it works for babies and toddlers who can’t describe what they see yet. It also works for individuals who might have trouble communicating because of a disability or medical condition.

The Cardiff Visual Acuity Test is also fantastic for situations where you want to get accurate results quickly. It’s non-invasive, meaning no discomfort for the child or adult being tested, and it doesn’t require a lot of cooperation, which can sometimes be hard to achieve.

Key Benefits of the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test:

No Talking Needed: Great for babies, toddlers, and anyone who can’t speak or has a hard time communicating.

Quick and Easy: The test is fast and doesn’t take long, so it’s easier for children to stay engaged and comfortable.

Accurate Results: The test gives reliable results, helping eye health professionals assess vision in a way that’s as accurate as possible.

Helpful for Everyone: Whether you have a young child or an adult who may have trouble with traditional tests, this one can help you understand their vision more clearly.

Who Can Benefit from the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test?

The Cardiff Visual Acuity Test is especially useful for young children. It’s also great for those with intellectual disabilities, who might not be able to communicate well enough for traditional vision tests. The test is one of a suite of tools used to make sure that everyone, no matter their age or abilities, can have their vision assessed in a way that works for them.

Conclusion

If you’re a parent or caregiver of a young child, or if you’re caring for someone with a disability, the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test is a wonderful tool to assess vision without needing them to speak or cooperate in the usual way. It’s a quick, easy, and non-invasive way for health professionals to ensure that their vision is healthy and that they are seeing the world clearly.

So, the next time you’re wondering how vision is tested for young kids or non-verbal individuals, you’ll know that the Cardiff Visual Acuity Test is an incredibly useful and reliable option that helps us get the answers we need to care for our patients' eye health.

Thanks for reading! If you want to learn more about how vision assessments work, feel free to check out my website or reach out for more information. I'm always keen to chat!

Employment and Vision Impairment

Image of a sign on a grass verge. The sign has the words “Now Hiring” printed in black on a white background, with a red border.

Despite disability laws, high rates of unemployment exist among people with vision impairment. In this blog post, I discuss some key findings from a recent review article entitled “Towards identifying gaps in employment integration of people living with vision impairment: a scoping review”.

How big is the problem?

Research across three developed countries, including Australia, Canada, and New Zealand demonstrate rates of employment among people with visual impairment of between 24% and 32%. These rates are less than half those for the sighted populations of those countries (64-84%).

Employment is a very important part of adult life. In addition to allowing a person financial independence and security, it affords social status, defines adulthood and identity, and allows people to make a meaningful contribution to society. Unemployment can lead to social, emotional, and psychological issues and overall lower quality of life. For people with disability, employment can also help to reduce their risk of social isolation.

What are the barriers to starting out in the workplace?

A plethora of issues were raised in this article, here are a few that stood out for me.

If we start at the very beginning, considering childhood experiences, many children with vision impairment are educated in mainstream settings. This is absolutely how it should be, but one consequence of this is that, because vision impairment is a low incidence disability group, visually impaired students may never have met another child or adult with visual impairment. This unfortunately deprives them of visually impaired role models, which for some, may have been hugely beneficial.

When it comes to choosing a career, preconceived ideas from within the sighted community can pose more limitations than the visual impairment, with students with vision impairment, frequently steered away from careers they may be interested in, and instead encouraged into ones perceived as feasible by the sighted adults around them.

Once a student with visual impairment has settled on a career, there are often challenges making the transition from educational settings into the workforce. We have disability laws to protect against discrimination, yet often, these are not well understood, and poorly implemented by prospective employers.

What about acquired vision loss?

Of course, not everyone with vision impairment has grown up visually impaired. People who acquire vision loss as adults face a different set of challenges. While they often do not lack work experience, they have to relearn how to perform their work. More years of experience, breadth of skills, leadership and seniority can be protective factors for retaining employment, but there are also employer-based determining factors. Generally, those working in medium to large workplaces, and in public roles, over private employment settings, are more likely to retain their employment.

Are we improving?

Maybe….?

Even right now, in a climate of labour shortages, people with visual impairment face challenges integrating into the workforce, so there is still a way to go.

Historically, people with disabilities were channeled into something called ‘sheltered employment/workshop’, which involved them being hired to specific roles and employed via a separate channel. Problems with this system were that it restricted options and often pay was not in line with the wider workforce. In most countries, including Australia, there has been a move away from sheltered work programs.

Things that help

People who have good social support are more likely to succeed in obtaining employment. Social support can be split into 4 categories:

Esteem support: encouragement and equal treatment from family, educators, workplaces, and the wider community.

Instrumental support: tangible aids and services offered through schools, rehabilitation organisations and workplaces.

Informational support: guidance in overcoming obstacles, information sharing, advice, and suggestions. This can come from parents, peers, role models, rehabilitation professionals, and workplaces.

Companionship support: strong connections with peers, family, and the wider community, extending to recreational activities.

What more can be done?

A collaborative approach would help. Schools and tertiary education settings need to help students with vision impairment to plug gaps and address skills deficits, to ensure they are viewed as eligible candidates (acknowledging that not all students with VI require this: some do just fine on their own). Ensuring full access to internships and career fairs which have been made accessible for people with visual impairment can further assist with smoothing the transition from study to employment. Employment agencies can play a role by assisting prospective employers to identify qualified candidates, capable of meeting their workplace demands.

More work is needed to address accessibility issues in the workplace, these include both physical and digital access. Whilst legislation exists to prevent this, in reality, there are often issues in implementation, resulting in barriers continuing to exist. Engagement of vocational rehabilitation professionals and eyecare professionals with prospective employers could also improve understanding of what true inclusion looks like.

Interestingly, the article highlights that rehabilitation practice often ceases once employment is obtained, with no follow-up. Continued support throughout the employment journey could allow for the address of issues which amount to workplace discrimination, potentially improving employment retention for people with visual impairment.

In conclusion

As with most things in low vision, multidisciplinary habilitation/rehabilitation is important. Professionals who may be involved include (but are not limited to): teachers trained in visual impairment, orientation and mobility professionals, vision rehabilitation specialists, assistive technology specialists, and occupational therapists. We need to ensure good social support from families, friends, colleagues, and the wider community. And we need to find a way to provide authentic role models for students with vision impairment. Of course, improving employment rates of visually impaired people would provide more role models for future generations.

Reference for the original journal article:

Ogedengbe, Tosin Omonye, Sukhai, Mahadeo, and Wittich, Walter. ‘Towards Identifying Gaps in Employment Integration of People Living with Vision Impairment: A Scoping Review’. 1 Jan. 2024 : 317 – 330.

Driving with vision impairment

Image of a lady (Belinda) wearing a bioptic telescope. She has red filter lenses on her glasses and is standing beside a white car, which is parked in a parking space, in a carpark.

A few weeks back I had the pleasure of meeting Belinda O’Connor. Belinda drives using a bioptic telescope. She was awarded a Churchill scholarship to travel overseas to learn about bioptic driving programs in other countries, and earlier this year, travelled around the USA and Canada, learning about how people are assessed for, and trained in the use of, bioptic telescopes for driving.

What is a bioptic telescope?

A bioptic telescope is a small telescopic device, which is mounted on a pair of glasses - we call these ‘carrier lenses’ - as such, the device can be used hands-free. Generally, the bioptic telescope is positioned at the top of the glasses, and the user will dip their chin down, and look up to view through the telescope when required. When looking straight ahead, they will be looking through the spectacle/carrier lens.

Image of Belinda wearing her bioptic telescope. Belinda has red filter lenses over her spectacles, and her pink bioptic telescope sits at the top of the spectacle frame.

What is bioptic driving?

A bioptic driver uses a spectacle mounted bioptic telescope to ensure they can see detail while driving. Most of the time, the person will look through the spectacle lens, which is where they have access to their full field of view - this is the full area that can be seen at any one time; you can find a fuller explanation of visual field in the first part of my previous blog post: Understanding field of vision: Why does my child climb up the slide, but then refuse to go down it? When the person tilts their chin down and looks through the bioptic telescope, they can see part of their visual field, magnified, and this allows them to discern smaller details than they can without the telescope.

Who benefits from bioptic telescopes?

Bioptics are helpful for people who have reduced visual acuity, or central vision loss, because they magnify things, and when things are magnified, they become easier to distinguish. Using a bioptic telescope will improve the best visual acuity that a person with vision impairment can attain. For a fuller explanation of visual acuity, you can read my previous blog post: What is visual acuity?

Bioptic telescopes can be used for any task where better visual acuity is required, and are particularly useful for distance tasks. Since they are mounted into a spectacle lens, they can be used when performing tasks where both hands are needed.

When considering driving, some people whose vision is not sufficient to allow them to meet the driving requirements can read the required line on the letter chart using a bioptic telescope. It is important to understand that to be eligible to drive, other aspects of vision, such as visual fields and contrast sensitivity also need to be considered. In addition, it is necessary to consider how a person uses their vision, because as low vision specialists, we know that two people with similar vision profiles may function quite differently from each other. Other aspects of a person’s general health must also be taken into consideration when determining fitness to drive.

Is bioptic driving safe?

In other parts of the world, individuals have been driving using bioptics for over 40 years. Research has shown that bioptic drivers’ performance is at least comparable to other groups of drivers considered at higher risk of collision (who are still legally allowed to drive), and at best, comparable to the general public.

It is also interesting to note that when we consider overseas experience, authorities that have commissioned research into bioptic driving have subsequently permitted it, and no jurisdiction that has implemented bioptic driving has revoked these privileges.

What did I learn?

It was a privilege to meet with Belinda and to hear about all she had learned during her Fellowship overseas trip. While there is little, if any research comparing different approaches to assessing and training people with vision impairment to drive using bioptic telescopes, experts in this field recognise the importance of carefully assessing multiple aspects of a person’s vision, not just their visual acuity, and considering how they use their vision overall, when determining who would be a good candidate for bioptic driving.

Belinda showed me the various adjustments that she has made to her vehicle to further improve her safety as a driver. She initially added a blindspot mirror to her car, which she found particularly helpful when learning to drive, and she has a digital display speedometer, so that she can check her speed easily. Belinda explained to me how, prior to a car journey, she will plan her route and carefully look over it, to identify any areas which might be challenging to navigate. As is so often the case with disability adjustment, I thought how very sensible; we would likely all be better drivers for following her example.

To finish up, Belinda took me for a short drive and explained her processes, regarding what she was observing and checking whilst driving. I learned a lot from Belinda and am so grateful to her for taking time out of her holiday up in Queensland to meet with me.

If you would like to learn more about bioptic driving, you can visit their website at: https://www.biopticdriversaus.com. They also have a Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/share/g/czkEFCfjsHQf8jpF/.

Prep vision screening

Last week I was invited to speak to the team of nurses who run the Prep Vision Screening program here in Queensland, about testing vision and eye health in children with complex disability and additional needs. We had a great session, with lots of really good questions. I thought I’d talk a bit about the prep screening program here in QLD.

'Butterfly' design occluding glasses used for testing vision in each eye at a time.

Who can access the program?

Any child enrolled in their Preparatory year within the state of Queensland can access the program.

What is the purpose of the Prep Screening Program?

If a child cannot see things clearly, then this will negatively impact on their ability to learn. The problem is that children are used to seeing the world the way they see it, and they may not realise if their vision isn’t clear, since this is just how it has always been.

Reduced vision can affect children's concentration, and coordination, and a lot of younger children won’t be able to articulate if they are having issues, instead, they may start misbehaving, so behaviour problems can be due to unidentified vision issues.

A further benefit of the program is to detect amblyopia. Amblyopia is where vision in one eye is reduced. It can often go undetected, because the vision in the other eye is good, and we don’t usually walk about with only one eye open.

What happens during the screening?

Children are asked to match letters on a chart and a small machine is used which takes a picture of their eyes.

What happens afterwards?

Results are sent to parents via the school. If a problem is detected, parents get a call from the nurse to discuss referring your child to an optometrist or ophthalmologist.

Does my child still need an eye test if they pass the vision screening?

Yes. The vision screening is a great program and helps to identify and treat lots of vision issues, but having a comprehensive eye test, where eye health can be assessed much more fully is always recommended.

What is school actually like for students who are blind / visually impaired?

I recently came across a journal article published in the British Journal of Visual Impairment, entitled “The participatory experiences of pupils with vision impairment in education”. Finally, someone though to ask the school students themselves about their experiences accessing education in a mainstream school environment.

Image of a classroom viewed from the back. Rows of students are seated at desks, facing toward a teacher at the front, who is standing in front of a chalkboard. One child has their hand raised to answer a question.

A generation back, in many countries, children who were blind or vision impaired would have attended special schools to receive their education. In most developed countries these days, a high percentage attend mainstream schools, reflecting a move towards inclusivity; the idea being that we should work towards making regular environments accessible to those with disabilities, as far as is possible, rather than providing separate facilities.

The study used a ‘qualitative’ approach, meaning that the researchers gathered the participants’ experiences, and perceptions. In this particular study, this was performed by means of focus groups. Thirteen students aged 8-18, who attended both primary and post-primary education establishments were interviewed. The article highlights that we still have a very long way to go to reach true inclusivity and provide an equitable educational experience for children who are blind or visually impaired.

The students reported adjustments not being made, or not being made fully, they also reported adjustments being made that were not actually helpful to them, based on assumptions and a one-size-fits-all approach. One student relayed how they were always seated at the front of the classroom, where the light from the projector really bothered them. This is a great example of why we need to consider each individual case: sitting at the front does generally help ensure good access, because when you get closer to things, you increase the angular magnification – they appear bigger, BUT, for some students, and some set-ups, there are other issues which may offset this, such as the light from the projector, or that the front quarter of the classroom is usually significantly dimmer than the rest, because of the projector placement. A student with significantly reduced visual fields may actually find it better to sit near the back of the classroom, since this will allow them to visually access more of the classroom at any one time. Another student reported being given work on a larger piece of paper, but the print on the paper was not enlarged. The result of this was to draw attention to the student, while not actually achieving anything. This is an example of school staff having good intentions, but lacking understanding and access to specialised knowledge.

A general lack of awareness was reported, which left students repeatedly having to explain their vision needs, while lack of forward planning on the part of schools often resulted in students having to miss breaks while staff attempted to resolve issues such as accessibility problems. Several students talked about the extra stress they experienced around exams when accessibility issues were encountered and last-minute solutions had to be devised, sometimes resulting in delayed starts to exams.

Image of children sitting around a table, writing in school books

Social isolation was another common theme. The students highlighted a range of issues, ranging from their lack of vision making it difficult to find their friends, or even to interact with potential friends, to their opportunities to socialise being restricted by the need to sort out access issues with technology and/or other teaching materials in their breaktimes. Activities, such as ball sports, undertaken by peers during lunch breaks, were a further source of isolation for some students, due to the difficulties they encountered participating in these activities.

School buildings are often old and incorporate minimal features to allow safe, comfortable access for people with disabilities. Students gave examples of a lack of high contrast markings for steps, directional material that was too small and low contrast for them to see, and hazards such as windows left open and bags left lying around, making safe navigation extremely difficult.

Overall, the article highlighted a need for a holistic approach, with improved awareness school-wide. It’s not enough for students with vision impairment to have to rely on a specialised teacher who they may only see a few hours every few weeks. On a daily basis, students who are blind / visually impaired attending a mainstream school will interact with numerous members of the school community, from other students, to teaching staff, to administrators. If we want to provide a truly inclusive environment, it is important for all of these people to have some knowledge and understanding about the needs of the student who is blind / visually impaired.

You can read the open access journal article that this blog is based on here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/02646196241268318.

What is Cerebral Visual Impairment?

Image: a picture of a human brain

September is CVI Awareness month, so here is a blog post discussing this common, but very under-diagnosed condition.

Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI) is the most common cause of vision impairment among children in developed countries, yet the majority of people, including health professionals, have never heard of this condition. Understanding CVI is a complex and challenging endeavor. In this post, I will attempt to provide an overview of Cerebral Visual Impairment, including a definition, common risk factors, diagnosis, and its functional impact for affected individuals.

When we think about vision problems, we assume issues lie with a person’s eyes. However, the most common cause of vision problems among children in developed countries is Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI), a condition which originates in the brain, CVI leads to a myriad of visual challenges. In this post we will take a closer look at CVI, exploring some of the complexities, and effects on individuals' lives.

What is CVI?

Cerebral Visual Impairment, previously known as cortical visual impairment, occurs due to damage or differences in the visual pathways and centers in the brain. This means that while the eyes themselves may be healthy, the brain struggles to interpret the information sent by them. It's like having a perfectly functional computer monitor (the eyes) connected to a malfunctioning computer (the brain).

Who is at risk?

Cerebral Visual Impairment is thought to affect 20-90% of children and adults with common neurodevelopmental conditions, including cerebral palsy, prematurity, and Down’s syndrome. People who have experienced brain damage, due, for example, to inflammation of the brain (meningitis), pressure on the brain (hydrocephalus), or blood/oxygen deprivation (hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy) are also at risk of having CVI.

Diagnosing CVI

Diagnosis can be challenging, as it requires specialized assessments by professionals familiar with the condition. Functional vision assessment is usually undertaken, which involves observing how the person uses their vision, and other senses, to access their environment.

Manifestations of CVI

CVI presents a wide range of symptoms, which can vary greatly from person to person. Some common manifestations include:

Difficulty with Visual Acuity: Individuals may have trouble seeing objects clearly or distinguishing details.

Visual Field Defects: Often people have difficulty seeing things in certain parts of their visual field.

Visual Motor Integration: Some people experience challenges in coordinating vision with motor skills, leading to difficulties with activities like catching a ball or navigating obstacles.

Complex Visual Processing: CVI can cause difficulties in recognising faces and facial expressions, objects, letters, and shapes.

Variable Visual Functioning: For many with CVI, visual abilities may fluctuate depending on factors like fatigue, environment, or other sensory input.

Impact on Daily Life

The effects of CVI can significantly impact various aspects of daily life:

Education: Children with CVI may struggle in educational settings due to difficulties with reading, writing, or understanding visual materials.

Social Interaction: Challenges in recognizing faces or interpreting social cues can affect social relationships and interactions.

Independence: Adults with CVI may face hurdles in tasks like cooking, driving, or navigating unfamiliar environments independently.

Emotional Well-being: Coping with the challenges of CVI can take a toll on mental health, leading to feelings of frustration, isolation, or low self-esteem.

Strategies and Support

While there is no cure for CVI, various strategies and interventions can help. Here are some examples:

Environmental Modifications: Simplifying visual clutter, using high-contrast materials, and providing consistent routines can make the environment more accessible.

Visual Aids: Spectacles, magnifiers, or electronic devices with accessibility features can assist individuals in accessing detailed visual material.

Educational Support: For school-aged children, working with educators who understand CVI and implementing personalized learning strategies is very important.

Therapeutic Interventions: Occupational therapy, orientation and mobility instruction, and other interventions tailored to address specific visual challenges can be beneficial.

Community Resources: Connecting with support groups, advocacy organizations, or online communities can provide valuable information, encouragement, and solidarity.

Advocacy and Awareness

Raising awareness about CVI is crucial to ensure that individuals affected by the condition receive the support and understanding they need. This involves:

Educating Others: Spreading knowledge about CVI among educators, healthcare professionals, and the general public can foster greater understanding and empathy.

Advocating for Inclusion: Encouraging inclusive practices in education, employment, and community settings can help create environments that accommodate individuals with CVI.

Empowering Individuals: Supporting individuals with CVI to advocate for themselves, assert their rights, and access resources that help them to navigate the challenges they face.

Conclusion

Cerebral Visual Impairment is a complex and often misunderstood condition that affects individuals in profound ways. More work is needed to raise awareness of the condition, both within Australia, and globally, because knowing who is most at risk, and getting better at recognising the characteristics of CVI, so that people can obtain a diagnosis is the first step.

I have been given a visual acuity, but what can my child actually see?

In this post, I talk about different levels of visual impairment, including a very simple example of how the different levels of vision would affect the task of viewing a face.

Sometimes, after an eye examination with an optometrist or ophthalmologist, you may receive a report containing a visual acuity. In a previous blog post I discussed how visual acuity is written, and what the numbers relate to, but what does it actually mean in terms of function? What can you see if your visual acuity is 6/24, for example?

Let’s think about some everyday tasks. What about recognising someone you know? Below is a clear image of a face.

Image: a girl faces the camera with a neutral facial expression. She has reddish hair in a bob-cut. She is standing against a backdrop of hills and a body of water, the background is out of focus.

This is how someone with a normal visual acuity would see a face. The features are clear and you could recognise the person if it was someone you knew. You can easily pick out their facial expression.

Now lets see what it looks like if you are visually impaired.

Image: the same image as above, of a girl with neutral facial expression, but this time, the facial features are slightly blurred

The above image is an approximation of what someone with a mild visual impairment might see; that is, an acuity of around 6/18. The images is less distinct, and it would be difficult to pick out subtle changes, but mostly, you can distinguish the facial features. Remember, this is for someone who is standing quite close to you.

For someone with moderate vision impairment, an acuity of around 6/24, it would look something like this:

Image: the same image as above, of a girl with neutral facial expression, but this time, the facial features are more blurred

At this level, it’s getting hard to distinguish the more subtle facial features, and if someone had a similar outline/profile, you could potentially mistake them. Again, bear in mind, that the person in the image is quite close; if we were trying to distinguish them from across a room, it would be very easy to mistake them for someone else.

Finally, lets look at how it might look for someone with severe vision impairment, that’s an acuity of around 6/60:

Image: the same image as above, of a girl with neutral facial expression, but facial features are only grossly visible due to the level of blur

At this level, facial features are not accessible. A person with this level of vision would be relying on other cues, such as voice, clothing, and context, to identify the person.

In Australia, people with visual acuity of worse than 6/60 are considered ‘legally blind’. It’s important to note that most people who are legally blind can still see some things, as illustrated above, it’s just that their vision is reduced enough that it is not considered useful in everyday life; they will need to use alternative ways to identify people, read, and get around safely.

This blog has provided just a single example of distinguishing a face, to demonstrate the impact of reduced visual acuity. But in every daylife, there are many, many other situations which are affected by vision levels. Consider, finding your food on your dinner plate, finding a toy in the toy box, or your door key wherever you last left it. What about telling whether the bus approaching is the one you are waiting for, or locating the toilets in an unfamiliar place?

For some more real-life simulations of reduced acuity, Next Sense have a Visual acuity simulations e-book that can be purchased for just a few dollars. If you are supporting someone with low vision, this can be a fantastic way to demonstrate to others involved in their care, how their vision impairment can impact on everyday tasks.

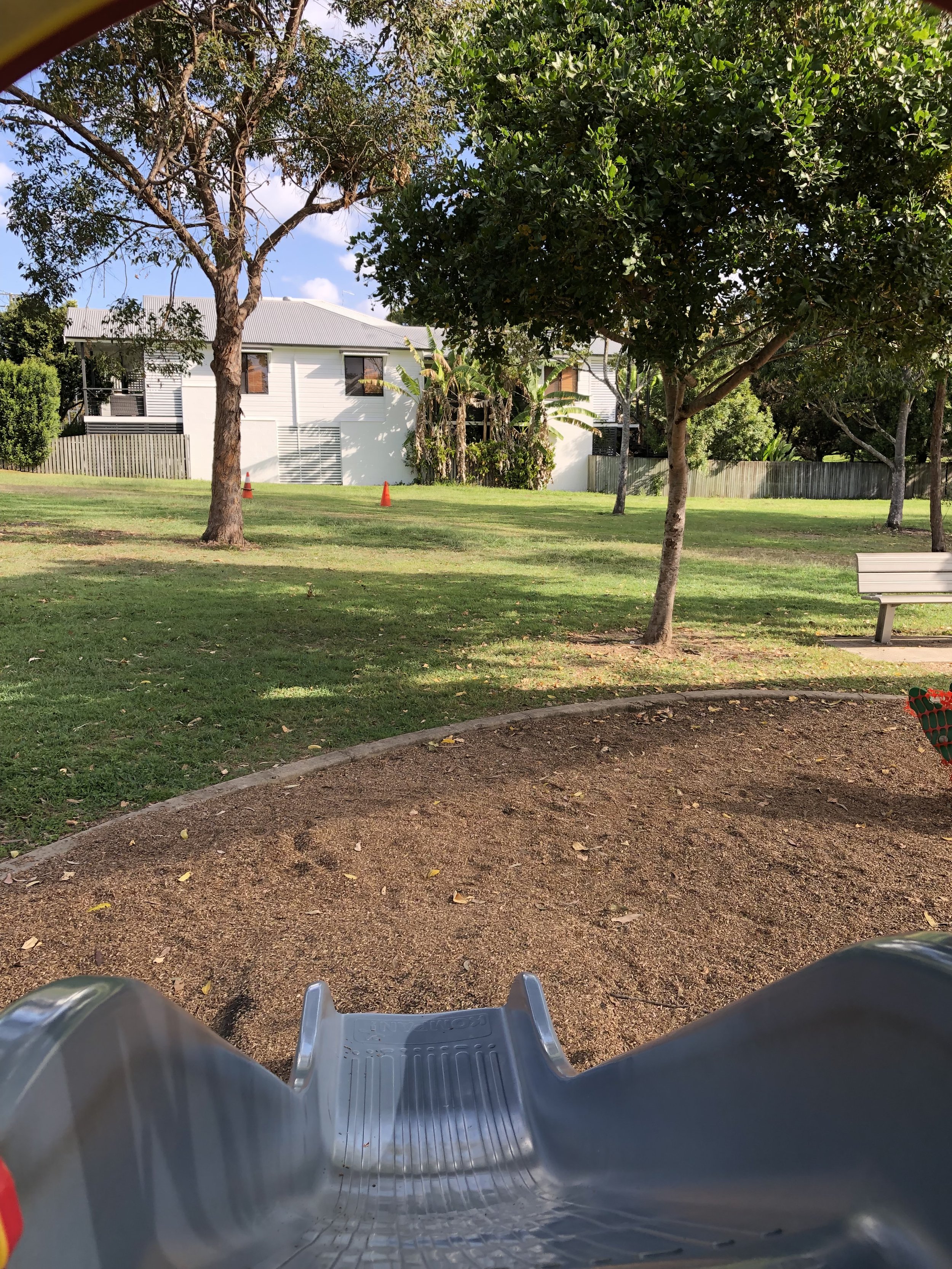

Understanding field of vision: why does my child climb up to the slide, but then refuse to go down it?

In this blog post I talk about field of vision: what it is, and the problems that can arise when it is reduced. This post focuses on lower field loss, which is very common in cerebral visual impairment.

Image: view looking down from the top of a grey slide onto the wood chip ground below.

In my last blog post, I talked about visual acuity, which is probably the most commonly recognised and used measure of vision. However, there are many other aspects of vision, besides visual acuity.

Visual field, or ‘field of vision’ is another very important aspect of a person’s visual profile. Visual field is described in the dictionary as: the entire area that a person is able to see when their eyes are fixed in one position. Where you are sitting right now, while reading this post on your computer, tablet, or phone, consider what other information is actually visible to you. While looking at the words on the screen, you are most likely aware of things to either side of you, and above and below you. Keeping your eyes on the words here, think about how far out to the sides you can see. You are probably aware of furniture within the room you are sitting in. If you are near a window, you will probably be aware of light from the window. If someone were to walk into the room you are in and approach you, you would notice them once they entered your field of vision.

For each eye, while looking straight ahead, we can perceive things out to around 100 degrees to our side, and about 60 degrees across the midline of our body. The below diagram attempts to illustrate this visual field

Image: on the left side is a bird's-eye view of a person, with a yellow arc illustrating a normal horizontal visual field for the left eye, extending from the eye, out to 100 degrees to their side (temporally) and 60 degrees across their body midline (nasally). On the right side is the same bird's eye view of a person, with a blue arc illustrating the corresponding horizontal visual field for the right eye.

Of course, we usually use both our eyes together, so our binocular field of vision extends horizontally out to around 180 degrees, and we can see things within an approximate semi-circle, where straight ahead is the 90 degree point.

Image: a bird's-eye view of a person, with the yellow arc representing left visual field, combined with the blue arc representing right visual field. The area where the two 'fields' overlap is coloured green.

In the above illustration, the area where the two ‘fields’ overlap is the area where we have binocular vision - we can see this area with both eyes, and it is by combining these two images that we are able to judge depths.

If you hold a finger out to each side and move it slowly behind you, you can get an approximate idea of the horizontal boundaries of your visual field, which should be similar to that pictured in the diagram.

Our vertical visual field extends around 60 degrees superiorly, and 70 degrees inferiorly

Image: a diagram of a person in profile with a grey arc showing their vertical visual field extending approximately 60 degrees superiorly, and 70 degrees vertically.

Various conditions can cause a reduction to our visual fields. One of the most common ones is glaucoma, which causes a gradual loss to our peripheral vision. The problem here is that, while our peripheral vision is very important to our visual function, most of us are surprisingly bad at noticing gradual loss of vision in this area. This is why having regular eye tests is so important, to check for changes indicative of glaucoma. Glaucoma can usually be managed successfully with eye drop medications, but if the vision has already been lost, we have no way of restoring it.

In people with cerebral visual impairment (CVI), we frequently find significant restrictions to visual fields. Many people with CVI have significant loss to their lower visual field. This causes a lot of problems for them because it is very difficult to get around safely when you can’t see in your lower field.

Here’s one example of why it’s difficult to get around safely when you can’t see things in your lower visual field. Below is an image taken in our building.

Image: Three tiled grey steps, leading down, in the foreground with contrasting edges and hand railings to each side, leading to a high contrast Braille mat. Beyond is a white wall with a clear glass door.

Now here is what it might look like if you have no lower field.

Image: the same image as previous, but with the lower half cropped, so the stairs are no longer visible.

With the lower field removed, we can no longer see the stairs or the Braille mat. We don’t know how many stairs there are, and we may not even realised that there are stairs if we are busy trying to get to the door.

For people with a lower field defect, getting up the stairs is easier. Let’s look at why that is.

Image: A grey tiled floor with a Braille mat, leading to three tiled grey steps, leading up, with contrasting edges and hand railings to each side. There is another high contrast Braille mat at the top of the steps.

When we approach the steps from below, they appear in our upper visual field. Let’s see how it looks to someone with a lower field defect.

Image: the same image as previous, but with the lower half cropped. The grey tiled floor is no longer visible, but the steps can be seen in the upper visual field.

From this direction, the steps are clearly visible and the person will be prepared for them.

Now consider it is a young child, or an adult with intellectual disability who is missing their lower field. They likely will not be able to articulate this issue to those who care for them. Parents and carers are left bewildered by the fact that the person gets up the stairs without issue, yet has so much difficulty going down the stairs, even the same stairs they climbed up! If you didn’t consider vision and understand visual field, this might seem like pretty confusing behaviour. Maybe you think the person is just being difficult. Or maybe you conclude that they just don’t like whatever is at the top of the stairs. Not an unreasonable conclusion.

A frequent report we hear from parents of children being assessed for CVI is that they will climb up the slide, but then either refuse to slide down, or will only come down head-first. Based on what we have previously discussed, does this behaviour seem a little less bewildering now?

Image: same as the first picture: view looking down from the top of a slide, but with the lower part of the image cropped, so you can no longer see the slide or where it leads to..

Once we understand that the issue is with the lower field, we can get help devising compensatory strategies. We even have specialised professionals who can help with this; they are called Orientation and Mobility Specialists.

What is Visual Acuity?

In this blog I explain about visual acuity; what it is, how it is measured, and how we categorise visual impairment based on it.

When you have an eye test, your visual acuity is one of the things that will be assessed, but what exactly is visual acuity? The term ‘Visual Acuity’ describes the smallest detail that a person can see when looking straight at a high contrast, stationary target. Visual acuity would be the most widely recognised measure of vision, though certainly not the only one, and not even necessarily the most important one (more on that in a future post). Visual acuity is usually reported in a standard format, and looks like a fraction where the nominator is usually ‘6’. The nominator tells you the distance the test was performed at, or is referenced to, while the denominator provides a comparison to the accepted ‘normal’ level.

The image shows a 6/12 fraction. There is an arrow connecting each number with a text box. The text box connected to the 6 nominator reads: this is the distance at which the person being tested was just able to distinguish the target. The text box connected to the 12 denominator reads: this is the distance from which a person with textbook normal vision would just be able to distinguish the target.

If your visual acuity is 6/12, it means that, standing at a distance of 6m, you can just decipher detail that someone with ‘normal’ vision could just decipher at a distance of 12m, i.e. you need to be twice as close (half the distance) in order to make out the detail, compared to the person with normal vision. 6/12 is classed as mild vision impairment.

6/6 is regarded as ‘normal’ vision. If you have 6/6 vision, it means that if you were to stand at 6m, you would be able to just pick out detail of a target that someone with ‘normal’ vision could also just distinguish at 6m. You may have come across the term ‘20/20 vision’, this is the American equivalent of 6/6, the same measurement expressed in feet, rather than meters.

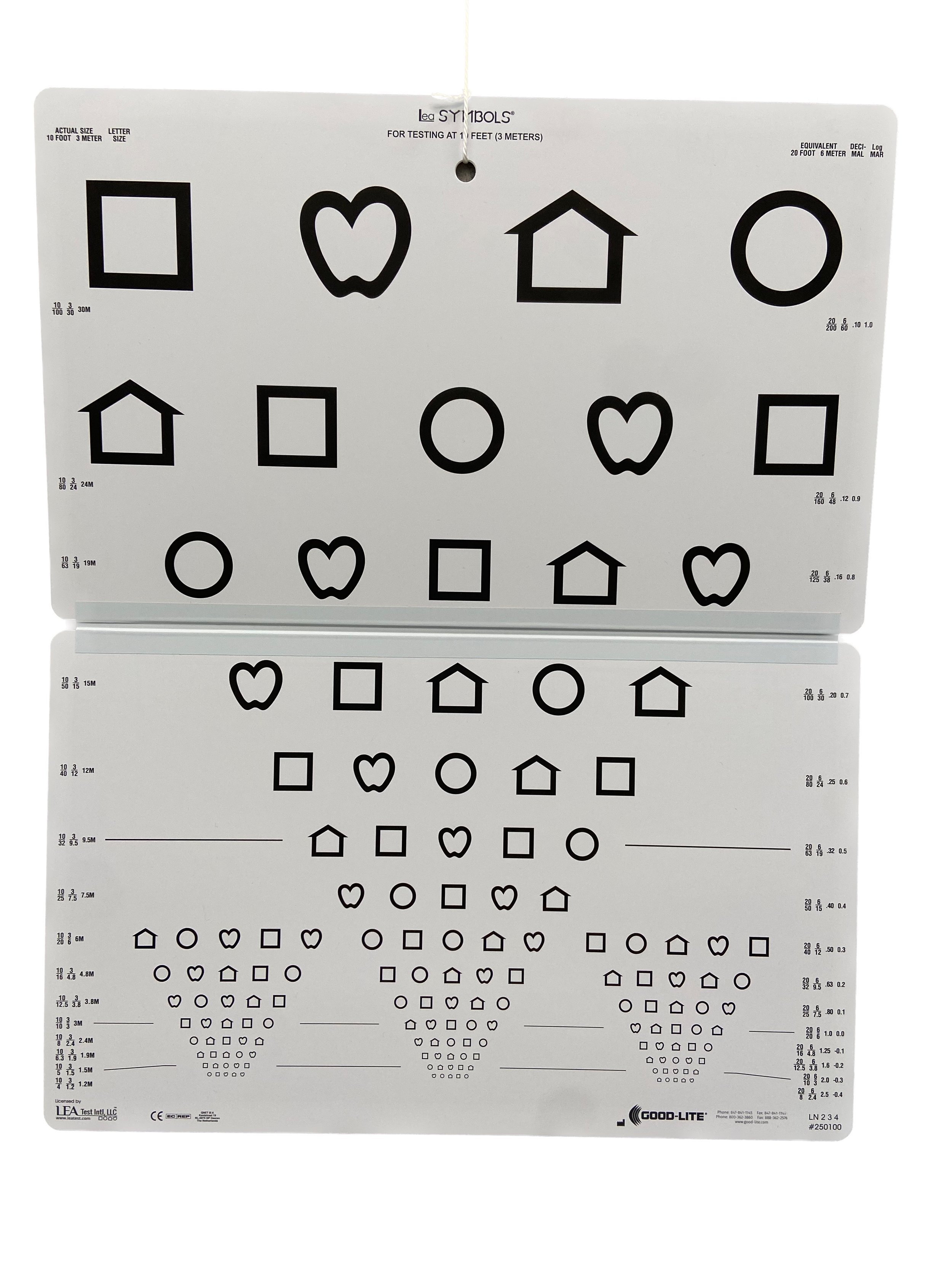

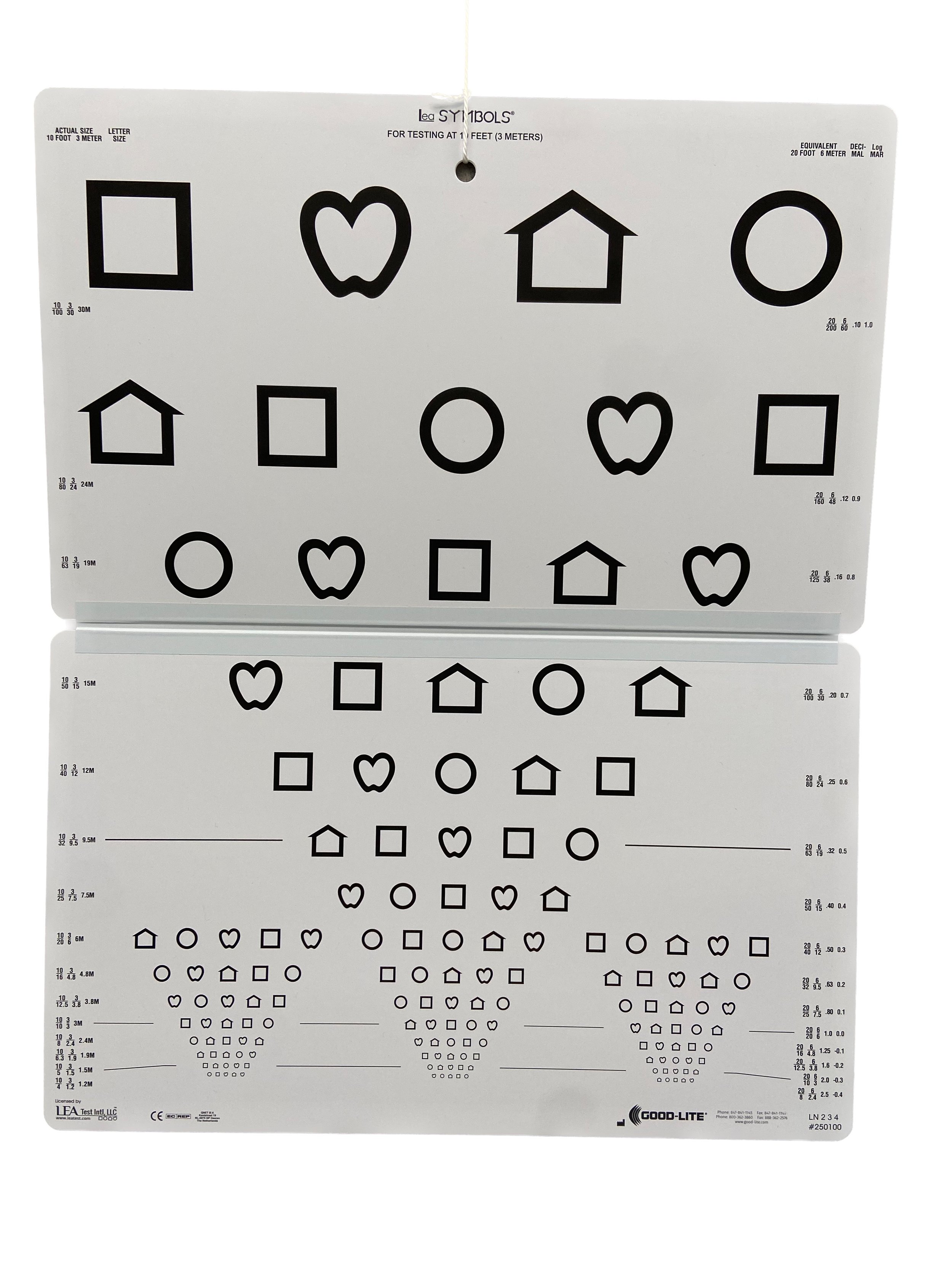

Testing at different distances

We don’t always perform testing at a distance of 6m, in fact, it’s pretty unusual to do so, since most optometry practices don’t have rooms that are 6m long, but because this 6-notation is widely recognised, we usually convert the acuity fraction to this format. Many optometry practices use digital acuity charts, which can be calibrated so that the letters or symbols are labelled with the equivalent 6m value, even though you may be being tested at a shorter distance.

Children usually perform better at closer distances, so most of the more traditional board-type acuity charts are calibrated for use at 3m. We can report the acuity for the 3m distance, or convert to 6m, or both. It is best practice to report the distance at which the testing actually took place, this is because, while the same letter presented at 6m will be exactly half the size of a letter presented at 3m and therefore equivalent in theory, in practice, vision is more complex than that, and there are various reasons why someone who can read a particular target at the 3m distance may not be able to decipher the equivalent size letter when presented further away.

Image of a Lea Shapes 'board'-type visual acuity chart. The Lea chart is designed for use at 3m, since this distance is better for children

We might test a child at 3m, and measure their acuity as 3/9. in this situation, we could just report an acuity of 3/9, or we could report the equivalent 6 notation acuity which would be 6/18. The best way to record this finding would be to state that acuity was measured at 3m and recorded as 3/9, which is equivalent to 6/18.

Monocular or binocular

We can measure acuity monocularly, or binocularly. Monocular means with one eye, while binocular acuity is with both eyes. In clinical settings, we would typically measure acuity monocularly, since we want to measure the vision in each eye, to make sure it is not reduced in either eye. If vision is reduced in one eye, this may be because the eye is short or long-sighted, or it could be a sign of eye disease, such as a cataract, or changes at the back of the eye.

Image of a little girl, sitting in an optometrist's chair. She is wearing plastic glasses with a hinged occluder attached to each side. Her left eye is covered by the occluder and she is looking towards the camera with her uncovered right eye.

In low vision settings, we tend to be more interested in binocular visual acuity, because we want to understand the person’s habitual level of functioning, and for most of us, we are usually using two eyes in everyday life.

Other acuity measures

Acuity charts that contain letters or shapes measure ‘recognition’ acuity, i.e. can you recognise the shape or letter. If someone is unable to access the typical ‘recognition’ acuity charts, we move to ‘detection’ acuity charts. For these assessments, we are simply determining if the person can detect a visual target, such as black and white stripes. These tests are essentially easier to perform, and as such, their results are not directly comparable. If someone were to perform both tests, they would likely score higher on the detection (stripes) test, when compared to the recognition (letter) test.

Image of three of the visual targets from the Lea paddles acuity test. Each target is shaped like a ping-pong bat, with a handle for the examiner to hold, and a circular 'paddle' on top. The left target is plain grey, the middle target has narrow black and white stripes, and the right target has wide black and white stripes

For this reason, it is recommended that the detection tests be reported differently. They are graded by the number of ‘cycles’ per cm, where a cycle is defined as one black and one white stripe. From the perspective of understanding a person’s level of functioning, it is more useful to know that they can just decipher high contrast black and white stripes of width 0.25cm, from a distance of 1m, because we can extrapolate this information into everyday life situations. If they have black canvas shoes with white laces, they will probably be able to see their shoelaces when they bend down. If they have a knife and fork with a black handle, placed on a white tablecloth, they should be able to find their knife and fork when they sit down to a meal, because the handles will be wider than 0.25cm. If someone is using a communication system, such as a PODD or PECS system, this information is essential knowledge; without it, we cannot be sure that the person can actually see the images they are being expected to use to communicate their needs.

Close-up of a 2 cycles per cm Lea paddle with a ruler placed on top. There are two 'cycles' of black and white stripes across a width of 1cm.

Vision vs visual acuity

When measuring what a person can see, we usually measure both with and without their glasses or contact lenses. We use the term ‘vision’ to describe their uncorrected acuity i.e. what they can see when they are not wearing their glasses or contact lenses. Visual acuity is the vision level when their refractive error (short or long sightedness) is corrected by glasses or contact lenses. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) is measured after we have determined a person’s script i.e. when they have the optimum correction.

So during a routing eye exam, we might:

Ask you to remove your glasses and read the letter chart: measuring your vision

Get you to read the letter chart with your current glasses: measuring visual acuity

Measure your refractive error and then get you to read the chart again: measuring your best corrected visual acuity.

Visual acuity levels

As discussed above, 6/6 is considered ‘normal’, and any fraction where the denominator is smaller, e.g. 6/5, 6/4, 6/3, is considered good vision. Someone with 6/9 vision would also be considered within normal range.

If a person has acuity of worse than 6/12, i.e. the denominator is 12 or bigger, then they are considered to be visually impaired.

A person with acuity of 6/12 to 6/18 is considered to have a mild visual impairment

A person with acuities of worse than 6/18 to 6/60 is considered to have a moderate visual impairment

A person with acuities of worse than 6/60 is considered to have a severe visual impairment

But, there is more to vision….

It is important to remember that visual acuity measures one particular aspect of vision. Some people can have normal, or near normal visual acuity, but because other aspects of their vision are not working as we typically expect, they may experience significant challenges to seeing. in a future blog post I will talk more about other vision measures.

If you are interested in learning more about eye tests for someone with complex disability and/or addition needs, please get in touch via phone: 07 3544 6167, or email: reception@specialeyesvision.com.au.

How do you assess someone who can’t tell you what they can see?

In this blog post I talk about the many different ways to assess vision if someone cannot read the letter chart.

Optometrist stands beside a visual acuity letter chart. She is pointing towards a letter using a stick with a red bead on the end.

If you have ever been for an eye test, you will be familiar with the standard procedure optometrists use for testing. We ask you some questions about your eye health and general health, eye history, and family history, then we ask you to read the letter chart. We usually ask something like “What is the lowest line of letters you can see clearly?” or “Please read this line of letters”. But what if you can’t read the letters? I don’t mean because they are too blurred, I mean because you have a disability that makes it impossible for you to read a line of letters out loud. Maybe you are non-speaking or minimally verbal, or maybe you have an intellectual disability and the task of reading letters is too complex.

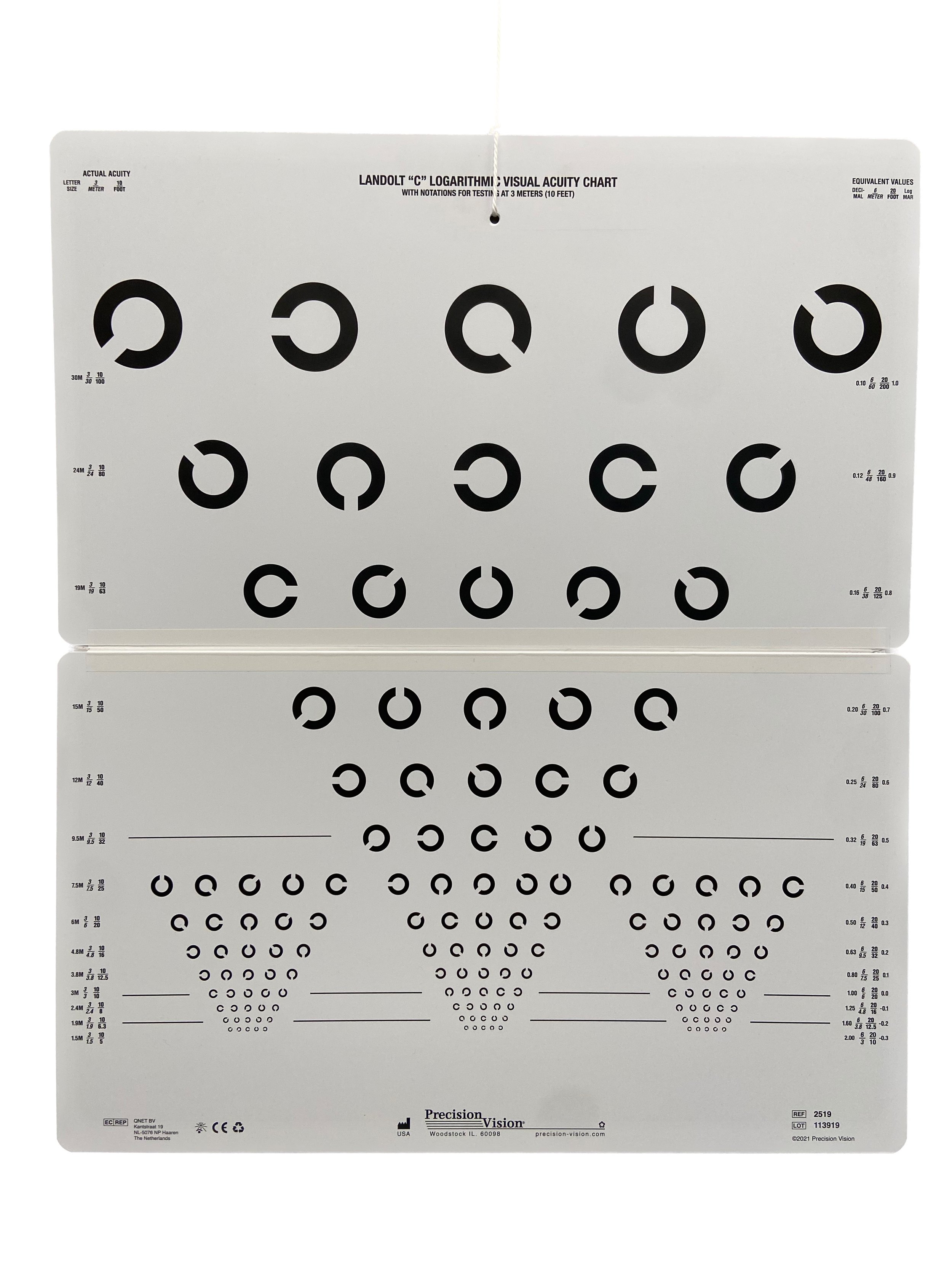

There are actually a lot of alternative methods for assessing vision. If the person being assessed simply doesn’t know the names of the letters of the alphabet, then we can use a similar chart, but with symbols instead of letters. The symbols can be named, or the person can match them using a matching card - “point to the same letter on your card”. There are also charts which comprise a single letter in different orientations, the task is to describe the orientation of the letter. Here are a couple of examples:

Image of the Lea Shapes visual acuity chart. The chart has shapes instead of letters. The shapes are a circle, a square, a house, and a heart/apple shape.

Image of the Landolt C visual acuity chart. The chart displays the letter C in different orientation

Naming shapes or reporting the orientation of a shape or letter does still require significant skills in addition to vision though, and for some people, these may not be a viable alternative. So what then? Well, don’t worry, we have yet more options. Preferential looking tests allow us to assess vision with eye gaze alone, ie. there is no need for the person being assessed to tell us what they can see. With these tests, the person is presented with a visual target which contains ‘detail' and another plain target. Here are some examples:

Image of the Cardiff Low Vision Acuity Test. There is a red box case in the background, and three cards are displayed in front, each card has an image of an apple. The apple is at the top of two of the cards, and at the bottom of the third. At the very front of the image there are two further cards, one has a picture of a ship at the top, the other also has a picture of a ship at the top, but it is almost too faint to see

The Cardiff acuity test consists of a series of cards, each with an ‘optotype’ (a picture) displayed at either the top, or the bottom. The image is created by an outline, which is made up of a thick white line, surrounded by two darker grey lines, each half the width of the white line. If the thickness of the line is too small for you to pick out, then the white and the dark grey with summate, to the same colour as the background, and the image disappears. This is referred to as a vanishing optotype. So how do we use it? The optometrist holds the card up facing the patient, and we observe where the patient is looking. If the person can see the picture, they will look towards it, because that’s just how all us humans are wired. The optometrist watches the patient’s eyes, if their gaze is directed towards the picture, we can be confident they have seen it, and we can conclude that their vision is good enough to distinguish the lines. If the patient cannot see it, we don’t see that clear directional gaze, rather the patient will continue to glance around the room at anything which catches their attention.

Image of an Optometrist holding up a Cardiff card with an image of an apple at the bottom

We present cards with lines of decreasing width until the purposeful gaze towards the picture is not longer observed. From this, we determine what the thinnest line is that the person can see, which in turn allows us to interpret their level of vision. The Cardiff acuity test can be referred to as a ‘preferential looking’ test, because we present a card with an image on one half, and we know that in most cases, people will look towards ‘something’ in preference to nothing, hence, if they can see it, their gaze will be directed towards the picture.

Another example of a preferential looking test, is the Lea Paddles, pictured below.

Image of Lea Paddles: each paddle consists of a circular target containing strips of varying widths with a handle for the examiner to hold. The front target is plain grey

With Lea paddles, we hold up one plain grey paddle, and one striped paddle. If the person we are testing can see the stripes, they will look towards those in preference to the grey, because they are more visually interesting. If they cannot see the stripes, they will glance between the two paddles, or just continue to look towards anything within the immediate vicinity which catches their attention. We reduce the width of the stripes until we no longer see that purposeful gaze towards the striped paddle, we identify the thinnest line the person can see, and this allows us to interpret their level of vision.

Image of an optometrist holding up two Lea paddles, one with wide black and white stripes, and one plain grey

All of the above tests are referred to as ‘standardised’; these tests have been carefully designed to ensure they are repeatable over time, and between different examiners. If you read a letter chart at your eye test one year, and then return for another eye test a year later, you should be able read the same line during each visit, even if you are tested by a different optometrist. If you can no longer read the same line, we know that something has changed and we need to find out what that is.

Standardised tests are always our first choice, but sometimes we have patients who just can’t engage with any of the above tests, and for them, we need to take a more functional approach. Functional vision assessment does not have the repeatability of standardised testing, results can vary from day to day, and you also might get a different result if you are tested by two different people, but it can still provide valuable information in terms of the level of detail the person can see. Actually, because it is more ‘applied’ or real world than standardised tests, it has some benefits over the standardised tests, I mean, how often do you actually need to read a line of letters in the distance, that don’t spell a word? And just because you can do this well, does it actually mean that you can function well visually? Sometimes people can see quite small detail, but still have poor functional vision for other reasons.

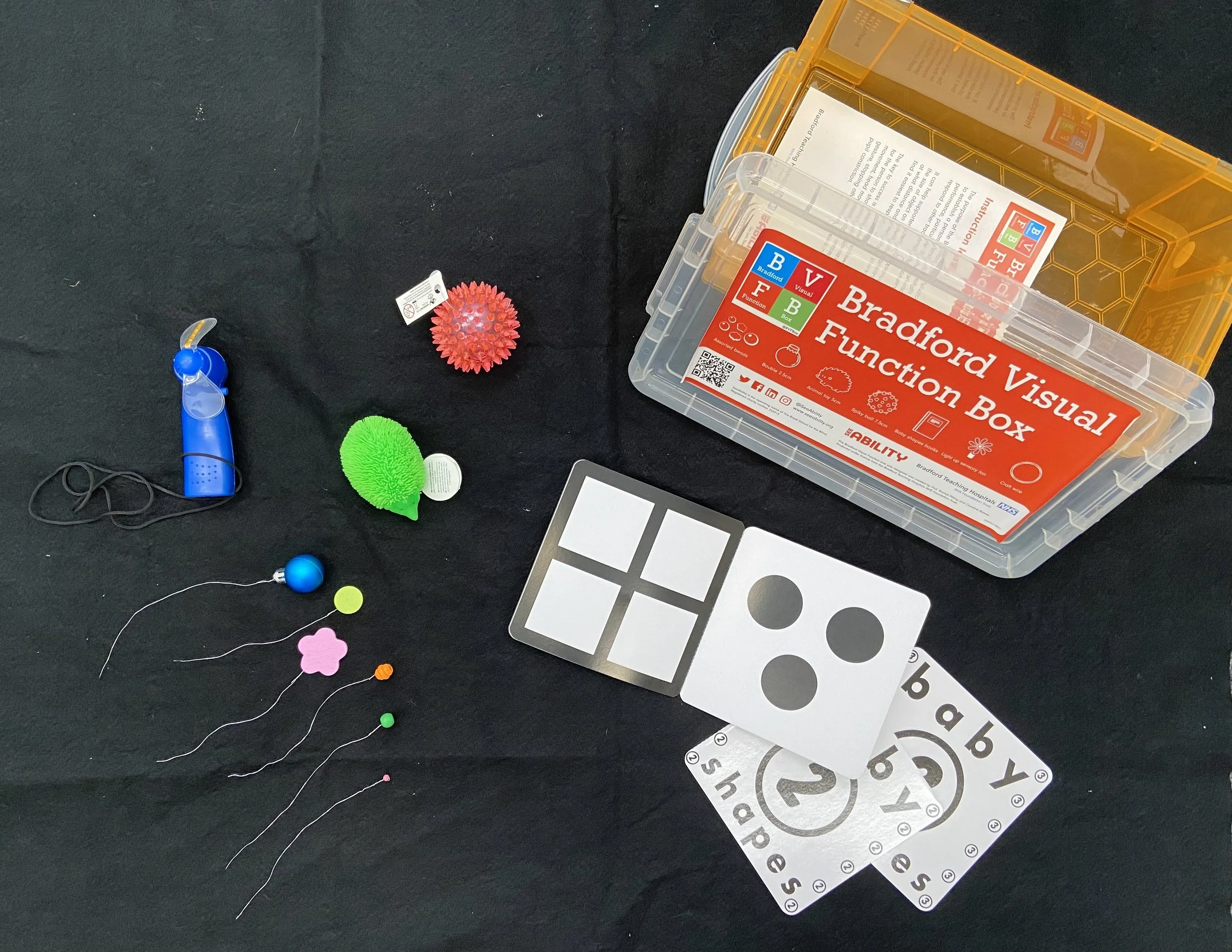

Functional vision assessment can involve monitoring whether or not a person can visually locate and follow a ‘target’ with their eyes. The target might be a small toy, a bead, a lollie, or a picture in a book. We can present different sizes of beads, and determine what is the smallest size bead that the person interacted with. The Bradford Visual Function Box is one example of a functional vision test.

Image of the Bradford Visual Function Box and contents including small brightly coloured toys, light up spinner, black and white baby books, and a series of brightly coloured beads of different sizes attached to bits of wire

The small toys and beads of varying sizes are presented, and we watch to see which the person visually interacts with i.e. which ones they look at. If they don’t look toward the item we are presenting, there is a good chance that it is too small for them to see. That is, providing we are presenting it in the right location: close enough, and in an area where the person’s best vision is located.

Image of an Optometrist holding up a small green bead attached to a thin wire

Assessing functional vision can be as simple as observing how a person navigates an unfamiliar space and what they chose to interact with. So even if someone have very limited ability to participate in our vision tests, we can still glean useful information regarding what they can and cannot see.

If you are interested in learning more about eye tests for someone with complex disability and/or addition needs, please get in touch via phone: 07 35446167, or email: reception@specialeyesvision.com.au.

How important is an eye test for someone with complex disability?

For families living with complex disability, an eye test can feel like yet another thing to add to their burdens, but getting your eyes checked is very important, and should not be an arduous process.

Young man with Down syndrome leaning in to touch noses affectionately with an older father figure.

Families living with complex disability already have a lot on their plate. They spend a lot of their time sitting in hospitals and specialist’s waiting rooms, so an eye test might feel like yet another thing to add to their burden. However, checking vision is super important and shouldn’t be an arduous process. Here are some reasons why it’s so important.

If vision issues are not addressed they can form a very real barrier

If someone has vision issues that have not been identified, they will be living with a sensory impairment - i.e. there is a barrier to their receiving input from their visual senses. Think about how much we use vision day to day. Around 80% of learning actually comes from visual input, so if you can’t see properly, then this is a huge barrier to learning and making sense of the world around you. If you have a child who is learning how to use a communication system such as a POD (short for Pragmatic Organisation Dynamic Display) or PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System), an undetected sensory visual impairment could seriously limit their progress in learning how to use this system. And when they don’t progress, will anyone think to check if they can see the symbols clearly? How would you even go about doing that if the person in question cannot communicate this information to you? In some cases, family and carers may end up giving up on the communication system totally, concluding that their child was just not capable, when a simple adjustment such as glasses, or changing the position of the device could have led to a very different outcome.

Vision issues are much more common in people with complex disability

Just like in the general population, some people with complex disability are short or long sighted, and these problems can be fixed easily through prescription of glasses. And yes, it is perfectly possible to measure what strength the glasses need to be, even in someone who cannot speak, we just use objective methods, which means we assess without the need for input from the person we are testing. Of course, if the person can provide any level of input, we will fully support them to do so, and this will be taken into consideration, along with our objective measurement.

Presbyopia also occurs just the same in people with complex disability. This is a natural process, which we all experience throughout our lifetime, whereby the crystalline lens inside the eye hardens, preventing us from being able to adjust our focus for different distances. Usually this is experienced as increased difficulty in seeing things at close distances, such as looking at pictures, reading, and locating personal possessions. Most people start to need reading glasses somewhere around the age of 40-45 years, so if someone has not had an eye test before, and they are approaching this age, an eye test is important to ensure they can continue undertaking near tasks that they enjoy.

In addition to the above mentioned causes of vision impairment, for any person whose complex disability affects their brain, such as brain damage occuring at birth, following prematurity, people born with global developmental delay, those with cerebral palsy, or Down syndrome, there is an increased risk of Cerebral Visual Impairment, or CVI. This condition can cause reductions in acuity - the level of detail you can make out, but also difficulties seeing in a particular area of your visual field, such as on one side, or in the lower half of your vision, below eye level. You might have difficulties seeing when the scene is complex, such as picking out the items you need from a supermarket shelf, or finding a friend in a crowd, or your might have difficulties processing more than once sense at a time, so if things get too loud, you become unable to process visual information and seeing becomes too difficult.

Image of a supermarket shelf displaying an array of different products.

People with complex disability are not able to tell you if there is a problem with their vision

Imagine if your vision gradually declined, but you had no way of communicating this to anyone. For someone living with intellectual disability, or with a communication disability, this could be their reality. Without the ability to convey their changed situation, they may just stop doing an activity which they previously enjoyed. Maybe everyone just assumes that they are no longer interested, when in fact, they have developed cataracts, which could easily be removed. Behaviour changes can be a clue that someone’s vision has changed, so this should be considered an indication that an eye test is needed in someone who is not able to communicate this information for themselves.

What does an eye test involve?

Having an eye test usually involves one or maybe two visits to the optometry practice. We can discuss beforehand how best to support the person having the eye exam and come up with a plan; we are also aware of the need to be flexible on the day and adjust as needed. If someone cannot answer questions or undertake tasks such as reading letters off a chart then there are lots of alternative methods we can use to determine what they can and cannot see.

Importantly, most recommendations following an eye test are for small adjustments to the person’s environment, rather than extensive therapy sessions. We might recommend that, when attempting to show the person something, it is best to present it within a particular area of their visual field - this is how far out to the sides, and above and below a person can see - since this may have been assessed to be where the person’s vision is most reliable. Similarly, we might highlight that someone needs to hold things very close in order to see them as well as possible. We might make recommendations for what would be the best lighting levels (lights on full, or reduced) and give advice on controlling glare. A few relatively small tweaks to the environment can make a surprisingly big difference. Of course, if we find that glasses would be beneficial, we will make that recommendation as well.

If you are interested in learning more, please get in touch via phone: 07 35446167, or email: reception@specialeyesvision.com.au.

Welcome to Special Eyes Vision Services

This is a blog post explaining the motivation behind my new venture: an optometry practice specifically to cater for children and adults with additional needs and/or complex disability.

A lot has been happening these last few months, and things are finally coming together. At this point, I thought it would be a good idea to talk a bit about the ‘why’ behind Special Eyes. There are lots and lots of optometry practices, but in creating this practice, I am aiming for something quite different, to service the needs of a very specific population. Here are some of the reasons for this venture.

Boy sitting in a wheelchair, he is smiling

Reason 1: I love working with people with complex needs